What I’ve learned about growth mindset from binging British reality TV competitions

Lately, I’ve been working on unhooking from praise and criticism in how I evaluate myself and my work. I’ve been examining my own unhealthy relationship to praise and how I’ve chased “gold star stickers” as validation for most of my life.

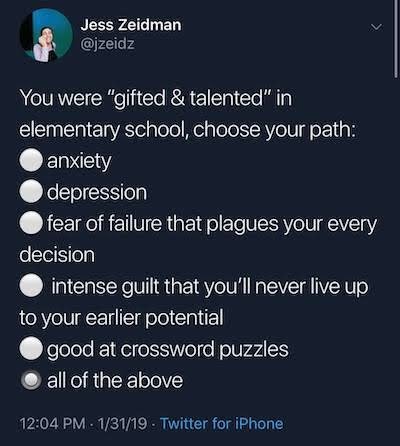

This started in elementary school when I would get praise for doing well academically. There’s a meme that made the rounds a few years ago that was so spot on for me, it made me cringe in recognition.

Oh yes, all of the above. 100%

The challenges that “gifted and talented” kids face later in life can be explained by Carol Dweck’s work on growth mindset vs fixed mindset. A growth mindset is where you believe intelligence is malleable and can develop and grow over time. A fixed mindset is one where you believe intelligence is fixed and static. It turns out that when we praise kids for specific abilities or achievements (“That was a great essay!”, “You’re so smart!” or “You’re such a good athlete!”) as opposed to attributes or intrinsic qualities (“Wow! I’m impressed at how hard you worked on that!” or “That was tough but I’m proud of how you stuck with it.”) we inadvertently stunt their growth mindset and drive them towards a fixed mindset.

Ability-based praise leads kids to believe that labels like “you’re so smart” are true for them and these attributes quickly become part of their self-identity. While this doesn’t seem bad at first glance, when we attach too strongly to something as part of our identity/ego, we then become terrified of it being stripped away. This causes us to default to a fixed mindset in order to preserve our precious identity and we learn to fear the inevitable failures that come as part and parcel of a healthy growth mindset. If trying something and failing becomes something that threatens who we think we are, then failure becomes a painful ego distortion rather than a normal part of learning and growing. The result is that the kids who were praised for abilities are much less likely to want to try challenging tasks than the kids who are praised for attributes, and are more often up for a new challenge.

As one of the “gifted and talented kids” my parents praised me up, down and sideways for my academic achievements. They bragged about it to friends. They told me I had such a bright future ahead of me as a result. They pulled me out of one school and put me into another to better match my intellectual prowess. It quickly became part of my identity and a great source of my self-esteem.

However, the problem with self-esteem is this — what happens when we can no longer do esteemable things? What happens when for some reason or another, we can’t perform at the level that we’ve come to expect?

Let me tell you, it feels like crap.

It feels like shame.

It feels like existential failure.

This became suddenly and abundantly clear to me when I lost a good deal of my cognitive function due to “chemo brain” almost overnight. My memory, information processing abilities, recall, vocabulary, and other markers of intelligence were all severely impacted by chemotherapy and I found myself unable to be the “smart kid” anymore. How could I be the smart kid when I couldn’t even process what someone was saying to me, let alone remember any information that would help me craft a response?

Common words eluded me. Facts and figures and ideas that I’d known by heart were murky at best. And my auditory processing was shot — if someone said something to me verbally rather than writing it down, I had no memory of it. Which made me feel like an idiot when I couldn’t remember something they’d said to me mere hours before. “Don’t you remember? We JUST talked about this, Megan.”

It was a huge slap in the face. And while I’ve recovered a good deal of my cognitive abilities, they’re still not what they used to be. But that sudden loss allowed me to look at my core identity as “the smart one” and how deeply it had been ingrained in my sense of self and ego. Only then could I look at whether that served me or not, and make some conscious decisions about what I wanted my self-concept to be.

So, what’s the antidote to this relentless quest for the gold star fix? And what does it have to do with British reality TV?

I realized after chemo brain hit me hard that I needed to shift my identity to be about attributes rather than abilities. For example, I have a thirst for knowledge and a love of learning rather than “I’m smart.” Or, I am compassionate, curious and open-minded about those in my life rather than “I’m a nice person.” Can I love reading and not be smart? Sure can! Can I be compassionate with someone’s suffering and still have good boundaries and say no? You betcha.

During the pandemic, I’ve been binge watching two British reality TV competitions: “The Great British Bake Off” and “The Great Pottery Throwdown.” These shows touch me in a way that I couldn’t quite name until one recent episode of “Pottery Throwdown.” One of the contestants, Roz, was asked to do a task that was way out of her wheelhouse. She finished the task but came in last in the judging. As she’s speaking to the judges about coming in last she says she’s embarrassed. Keith, one of the judges, looks at her with tears in his eyes and says, “Never feel embarrassed, Roz.”

What he’s saying to Roz here is that she should be proud of herself, she should be proud of her attributes of persistence, resilience and grit rather than be embarrassed about her abilities (or lack thereof) at this specific task. You can see the interaction here:

My love of these British reality competitions comes from the culture on these shows of being proud of trying your best, going out of your comfort zone, and being resilient and gritty. These are valued more on these shows than whether you came first or last. It’s not about the gold star or the winner’s ribbon, that’s just icing on the cake. (Yes, I made a baking pun, just for you my fellow GBBO fans.) The core values of these shows are about how extraordinary it is for people to show up with uncertainty, put in the effort, and try something new without knowing how it will turn out.

No wonder I love these shows, they’re models of growth mindset that I desperately need. They feed the part of me that wants to see this in action, the part of me that wants to soak up all of these examples of how to value attributes rather than abilities like a sponge so I can turn around and do the same for myself and others.

Here’s my challenge for you this week — try to think of a time when someone praised you for your attributes rather than your abilities. What did they say? How did it feel?

If you can think of one, please comment on this post or email me at megan@megancaper.com and tell me about it. Like I said, I need more models and ideas for how I can do this more for myself.

Xo Megan

P.S. For more on this subject: